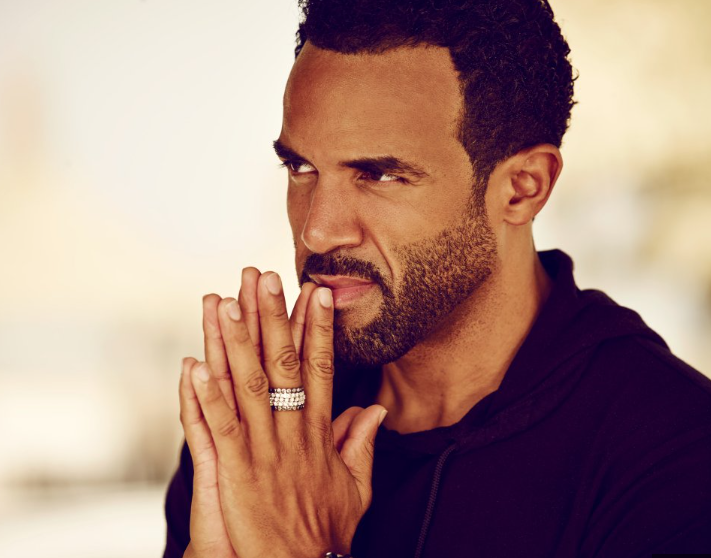

As the new millennium approached, U.K.-born singer Craig David had no idea that he would soon dominate the worlds of R&B and pop. At just 16 years old, this gifted and ambitious songwriter crafted a series of tracks that would eventually become chart-topping hits on the Billboard Hot 100—laying the groundwork for a career marked by numerous musical achievements.

Released in 2000, David’s debut album Born to Do It made a seismic impact on the R&B scene. With his slick, flowing vocals and a strong grasp of U.K. garage, he stood out as a vibrant and unconventional artist both in the UK and internationally. Tracks like “Fill Me In,” “7 Days,” and “Walking Away” demonstrated his remarkable talent as a singer-songwriter, seamlessly blending catchy melodies with lyrics that felt both smooth and precise. The universe rewarded David’s “labor of love” many times over: Born to Do It spawned two top-15 hits, with “7 Days” breaking into the top 10 of the Hot 100 and earning him a Grammy nomination.

With influences woven into his DNA—drawing from the likes of Notorious B.I.G., Bone Thugs-N-Harmony, Joe, and Usher—Craig David set a new gold standard for the dawn of the new millennium. His masterpiece didn’t merely revitalize R&B and pop; it also empowered the U.K. artist to remain bold and innovative throughout his more than 20-year career, constantly pushing creative boundaries and exploring new musical horizons.

“I believe the key message is to cherish your album as much as you did when you first created it,” David shared over Zoom last week. “While we’re always eager for new music, each album is like a child—something special. It’s important to appreciate all of them equally because Born to Do It continues to be a gift that keeps on giving. I love it just as much today as I did when I first made it.”

As part of Billboard’s Black Music Month celebration, David spoke with Billboard about the 25th anniversary of Born to Do It, the creation of his iconic tracks “7 Days” and “Fill Me In,” and more.

“Before signing a record deal, I was already working on what would become Born to Do It,” he recalled. “Do you remember which early songs helped shape the album’s foundation?”

He explained, “I was living in South Hampton, in the U.K., and I grew up in the projects. For me, it was about a ten-minute walk to this one area where the studio was—where I’d work with Mark Hill, who produced and wrote the album with me. It was really a labor of love. There was no pressure, no strict timeline. If we wanted to write a melody today, cool. If we preferred to do lyrics tomorrow, that was fine. It was all very relaxed.”

“‘Rendezvous’ was one of the first tracks I worked on alongside ‘Walking Away.’ I remember taking my time with it. Mark was playing this beautiful harp, and I went back to my bedroom, letting that harp loop on repeat. [Starts singing “Rendezvous”] Then I’d go back into the studio, where he’d add harmonies. For me, that process exemplified what music should be—before it becomes about the business side of things. It was all about the music itself.

At the time, I was also a DJ, making mixtapes. I was always thinking about how this track could sit alongside songs like Usher’s ‘You Make Me Wanna,’ or blend smoothly with Joe’s ‘Table for Two’ or Tank’s ‘Maybe I Deserve.’ Living in that world, that was everything to me. So, when people connected with it, I was genuinely hyped, you know what I mean?”

When you and Mark Hill were in the trenches, what did that era teach you about creativity before the industry got involved?

You know, we were at a time when analog was starting to give way to digital. Pro Tools wasn’t really around back then. Mark was using this software called Studio Vision, which didn’t have all the features we now take for granted with Logic or Pro Tools. One thing I really appreciate about Mark Hill—especially when I listen back to that album—is that he originally was part of the Welsh Philharmonic Orchestra. He has a background in playing real instruments and loved to play percussion, which added a lot of depth and authenticity to our work.

When you went into the studio, he approached it from a very different angle compared to some of the R&B and hip-hop you were listening to at the time. It was more live, but you had time. What’s the biggest takeaway from that experience?

I think the biggest lesson was time. Nothing felt rushed; everything had a moment to live and breathe. That allowed us to come back and say, “You know what? Maybe it’s not quite right the way it is. Let’s tweak it.” As a DJ, I did many iterations of “Rewind” by playing the track in clubs—sometimes to 100-150 people. I’d listen to how it hit the crowd, notice if the bassline took too long to drop or if the bass wasn’t quite right, then go back, make adjustments, and test again. This process could take months, but eventually, you’d have the perfect version of the song.

I feel like I haven’t really changed with social media and the fast pace of today’s industry because I still believe in quality over quantity. When you hear a big tune blasting through speakers, you never forget that feeling.

Colin Lester heard “Walking Away” and “7 Days” and decided to upgrade you from a developmental deal to an album deal. How did that elevate you and motivate you to deliver on your debut album?

I didn’t even really understand what a development deal meant at the time. I was just walking into various record labels across the U.K.—places like Epic, Columbia, BMG, Arista, Warner, RCA, and Atlantic. I remember seeing these glossy walls, shiny floors, and big plaques from artists I’d grown up listening to. You know, you look at it and think, “I want to be part of this,” it’s inspiring.

What stood out too was what people were saying about me: “There’s this 16-year-old kid with a song called ‘Walking Away,’” and they’d ask, “Okay, we’re in the game, but where is it heading?” In my mind, I was thinking about “Rewind”—which, at the time, was the only song forcing its way onto both radio and pirate stations. It was massive in the clubs. And “Walking Away” was sitting right there, gaining momentum. When I went into Wildstar, Colin Lester’s record label, he looked at me and said, “Based on ‘Walking Away,’ if you can write lyrics like that at 16, then what are we developing here?”

Everyone was talking to each other, by the way. He’d tell other A&Rs the same thing they were saying, effectively throwing them off the scent. He confided in me afterward, saying, “Yeah, I told them you might have one song, and I wasn’t sure.” Clever guy. Then he said, “Craig, I’ll do an album deal with you off the bat.” I remember a few weeks later dropping off a little gift with “Fill Me In” and “7 Days,” and he came through on that album deal exactly as promised.

How did your time with Artful Dodger shape your musical instincts when you were working on Born to Do It?

Growing up in South Hampton, I felt that it wasn’t a city known for its musical exports; everything was very London-centric at the time. Working with Artful Dodger was a game-changer. They started gaining recognition with some club performances in London. One of the first songs I did with them as a featured artist was “What You Gonna Do.” I’d go up to London, sometimes paying my friends 50 pounds to drive me in their little Fiesta so I could perform at the Coliseum.

I started making a little money and was also doing the DJ thing. Their rise was so inspiring—especially with tracks like “Too Fast” featuring Romina Johnson. When “Rewind” dropped, I realized I’d learned a lot from their hustle. We couldn’t just stay in South Hampton and wait for someone to discover us; we had to physically take the music out and put it in the shops. I respect both Mark Hill and Pete Devereux for that. They had different personalities—Mark was more of the musical genius, while Pete was the DJ.

Was the album title loosely inspired by Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory?

Is it true that the album title was loosely inspired by Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory?

Yeah, my guy. Still a classic in this household. I’ve been watching that movie since I was a kid. There’s something about the way Charlie comes from a working-class family and didn’t think he’d ever have a chance to win a ticket. He didn’t have the same money as others, but he stuck with it. He stayed persistent and did the right thing.

Suddenly, he gets to live his dreams. And when you reach the end of the movie, he still has the values and morals to say, “Even though I could sell this Everlasting Gobstopper right now, I’m gonna put it back on your desk, Mr. Wonka. I appreciate you. You’re the guy.”

In the opening scene, the kids rush into the candy shop, and they ask the candyman, Bill, “How does he do it?” Bill responds, “My dear boy, do you ask a fish how it swims?” The boy says, “No.” Bill continues, “Do you ask a bird how it flies?” The boy agrees, “No, surely not.” Bill says, “They do it because they were born to do it.” That really stuck with me, yeah?

By the time I was working on the album, it was almost a given that it would be called Born to Do It. The funny thing is, the album cover came from a few shots we took at the end of a long day of shooting. A headphone company at the time offered us free headphones and asked if we could snap a few quick photos. We agreed, just for an internal office shot. Later, looking back at the photos, we thought, “Yo, this one with you holding the headphones and looking up—seeing Born to Do It—that’s pretty dope.” That ended up being the cover.

Your first single was “Fill Me In.” How did its reception differ between the UK, where it was first released, and the US?

After the success of “Rewind,” I could already feel the anticipation building. “Fill Me In” was always my tune from day one. I remember thinking, “I can’t wait for this to drop.” (Starts humming the song) The guitar riff alone? Forget everything I did on it—this thing is crazy. Certain guitar licks just command respect. Like John Mayer’s “Neon”—you hear that riff and it just hits different. You don’t need much else; the guitar speaks for itself.

People started to vibe with “Fill Me In” because it had this garage feel but also a strong R&B influence. My flow was inspired by artists like Twista and Bone Thugs-N-Harmony—anyone who could spit that fast. Beyoncé, in her early work, had that cadence—she could ride a melody and rap with speed. Blending melody with that rapid-fire flow felt natural for us. It was real talk, but the way I performed acoustically in the UK really opened people’s eyes.

Before I came to the US, I think the UK saw me as more of a garage artist, but when I performed it acoustically here, they realized, “Okay, he’s got some R&B in him. It’s not just garage; it’s got pop and R&B elements.” Once I came to the US and we shot a new video for it—my first time in Miami—that changed everything. That moment hit differently. The US embracing it was a huge step because garage music was primarily a UK thing. Seeing it translate across the Atlantic was a big deal.

QYou released two different versions of the “Fill Me In” video — similarly with “Walking Away.” Which version of “Fill Me In” means more to you today?

I still think the original from the UK holds more significance for me. Don’t get me wrong, I grew up immersed in US R&B and hip-hop. I was that guy—vinyl collector, deep into the culture. The first video, where I was doing a pirate radio station setup as my opening vibe, reenacting being on the side of a building and hiding from my dad—that was my first real moment in visuals. It was my debut. When I got to Miami, everything changed. I was hearing Black Rob’s “Whoa” and Carl Thomas’ “I Wish” at the same time. I thought, “This is a wave,” and here I was, shooting a video in Miami. It was wild.

What about “Walking Away”?

Yeah, I gotta say the UK version. There was something powerful about getting out of the car in the middle of traffic and walking down the street. I felt so much in that moment. I was stuck in traffic, and the song was kicking off in the car. Instead of just riding it out or entertaining the situation, I had the audacity to leave the car, walk away—literally at my breaking point. That moment was crazy.

“Last Night” was a slept-on favorite, especially with you rapping on it. That was rare for R&B artists back then. What made that song the right moment to showcase that side?

You know what’s funny? I actually wrote “Last Night” before I even dropped “Rewind.” For me, it felt like a remix of sorts. It’s crazy because I was able to take a verse from “Last Night” and be singing that while making “Rewind,” and it all just fit so well. I remember thinking, “I don’t want to make something too different,” so I asked, “Can we just use this verse and tweak a couple of words?” As you said, “Last Night” was really ringing off, and the vibe of it was just right.

You added two more tracks to the U.S. version with “Fill Me In Pt. 2” and “Key to My Heart.” What made you decide to go that route?

It sounds like making the U.S. version of your album involved some tough decisions. Can you tell me more about that process?

Yeah, it was a difficult choice. I knew I needed to add something for the U.S. release to give it a little extra boost. The label wanted a couple of new songs to help strengthen the album. Since Born to Do It had already been out for a while, I thought, “Okay, it’s gotta feel like it belongs.” It’s tricky when you have a body of work that’s been out and you try to add songs to make it fit together seamlessly. So I worked with Jeremy Paul, who produced “Key to My Heart.”

The cool thing was, I’d already had the melody for “Key to My Heart” around the same time as Born to Do It. It wasn’t like it couldn’t have been with Mark Hill if I’d wanted, but when Jeremy sent over the instrumental before we even met, I already had the melody in my head. It felt like it belonged in that world.

As for “Fill Me In Pt. 2,” that was originally done in the UK. It was already gaining popularity alongside the “Sunship Remix” of “Fill Me In” and “7 Days,” so it still felt like part of the same project. It was tough to insert new songs into an already established body of work without it feeling like a tag-on, but the UK audience kept asking, “Why didn’t you add ‘Key to My Heart’ to the original?” So, it all worked out.

You follow “Fill Me In” with “7 Days,” which was Grammy-nominated and peaked at No. 10 on the Hot 100. To you, what makes that song so beloved?

I think “7 Days” is the gift that keeps on giving. The way Mark Hill and I wrote that song, I was in awe of his guitar playing. You already gave me “Fill Me In”—you had me at hello. Mark would even tell you he’s not really a guitar guy, but last I checked, he’s definitely the guitar guy.

When we made “7 Days,” I was blown away by the melody. We were both fanboying over each other’s musical skills. When it finally dropped, I remember seeing the response from fans—especially during the album’s promo period, when I was playing it before release. Nobody else had it yet, so the fact that people responded so strongly—saying, “This is a vibe, this is a tune”—it was incredible.

The music video, inspired by Groundhog Day with Bill Murray, was directed by Max and Dania, who nailed it perfectly. In just three and a half minutes, they managed to capture all these iconic moments—kids running around, catching shoes, me waking up and checking the time, the woman with balloons, the guy setting up papers, and me in the barbershop. Everyone could relate to it. It was so blessed, man. Like you said, I wholeheartedly agree—the visuals, the music, and how it continues to live in conversations make it special.

Wasn’t there a story about you having the “Foolish” beat before Ashanti’s remix?

Yeah, I remember when Irv Gotti sent over that instrumental, trying to do a remix for “7 Days.” Back then, Ja Rule and Ashanti were blowing up with “Always on Time.” I had the DJ Premier remix of “7 Days,” but I also had this instrumental sitting on my computer. I thought, “How should I approach this?” Because my favorite song at the time was Biggie’s “One More Chance,” with that same DeBarge sample. Every time I heard that guitar riff, I instantly thought of it.

But somehow, it fell by the wayside. I didn’t follow up quickly enough, Irv moved on, and I lost the moment. Then I heard Ashanti’s “Foolish,” and it hit hard—became a monster hit. I was actually hoping that instrumental could turn into “7 Days,” but I’m glad it didn’t work out that way. What they did with “Foolish” was incredible, and I’m happy for that song’s success.

That Mos Def and Nate Dogg remix flew under the radar for some, but it was major. How did that collaboration even come together?

I mean, DJ Premier—Gang Starr, “Nas Is Like,” “10 Crack Commandments”—he was the guy. Everything he touched just hit differently. The way he pulled the song together on his MPC 60 was next level. When I first came to America, I was in New York and got the chance to go to the studio and meet Premier. I was super hyped. Watching him pull up records, do his scratches—I was like, “This is DJ Premier!” I took that energy back to my hotel room and ended up recording most of the vocals there.

What’s crazy is, I wasn’t even using the best equipment. Just an okay microphone going into my basic DI-box interface. But then, Mos Def’s “Mr. Fat Booty”—that was my joint from my guy. As for the Nate Dogg one, that was wild because the vocal that ended up on the track was me trying to emulate Nate Dogg’s style. I was just trying to bring those two worlds together. It was a vibe.

Twenty-five years later, your album still has a reverence and freshness. Why do you think it’s aged so well?

It’s really tough when you’re in the eye of the storm, but when I was making that album, I had all the time in the world. It was a labor of love—no rush. Everything had its place. Every melody, ad-lib, was carefully crafted. I think the chemistry between me and Mark Hill was so special because we complemented each other perfectly. I was an R&B/hip-hop head who loved the DJ elements, and he brought that musicality with his Philharmonic Orchestra background, pulling out all the stops. We just clicked.

Maybe we weren’t trying to replicate everything else out there. When I hear Rodney Jerkins talk about making Whitney Houston’s “It’s Not Right, But It’s Okay,” or when he says, “I came over to the UK and heard Craig David’s ‘Fill Me In’ ringing off in the club,” I think about how those moments are so inspiring. Rodney’s work on Gina Thompson’s “Things You Do,” Brandy’s “Full Moon”—those are legendary moments. It’s a blessing to be part of that wave, and I hope those moments keep happening for artists everywhere.